For those of you who have seriously missed baseball during the pandemic, my friend César Love has an unusual and intriguing book--Baseball: An Astrological Sightline. Not your average account of the sport, this is an examination of baseball's magical quality, its spiritual aspect. Baseball: An Astrological Sightline uses astrology to demonstrate the transcendental nature of the game, showing how the stars and planets "affect the course of every baseball season and every baseball game." If you've wondered why the Cubs seem accursed or why the Mets were miraculous in 1969 Mets, César offers answers with astrology as a lens.

Love baseball but don't believe in astrology? You still might find this an interesting book. César, a poet and journalist as well as an astrologer, is a serious baseball fan, so there's lots of baseball lore here. As Kim Shuck, Poet Laureate of San Francisco and author of Deer Trails and Smuggling Cherokee, notes, "César Love takes a very fresh view of the histories of the various baseball teams. Poetic, beautifully written and researched, this book is a great read for baseball fans, historians and those interested in astrology. An absolutely unique piece of writing."

Tuesday, March 30, 2021

Friday, March 19, 2021

Prague and Beyond: Jews in the Bohemian Lands

New books are coming out in profusion! Here's another title of interest: Prague and Beyond: Jews in the Bohemian Lands, edited by Kateřina Čapková and Hillel J. Kieval. While you may need to wait to get the hardcover, it looks like the e-book is already available.

I'm being very quick-and-dirty about posting this as I'm in the middle of the annual Czech and Slovak Studies Workshop, hosted by University of Pittsburgh this year. It's free to sign up and attend and continues through Sunday.

I'm being very quick-and-dirty about posting this as I'm in the middle of the annual Czech and Slovak Studies Workshop, hosted by University of Pittsburgh this year. It's free to sign up and attend and continues through Sunday.

Tuesday, March 16, 2021

Prague: Belonging in the Modern City

I'm pleased to report that fellow Czech specialist Chad Bryant's new book Prague: Belonging in the Modern City will be out in May. In Prague, belonging has often been linked to a sense of nation. Grand medieval buildings and national monuments emphasize a glorious, shared history. Governmental architecture has melded politics and nationhood. Yet not all inhabitants have been included in this nurturing of national belonging. Socialists, dissidents, Jews, Germans, and Vietnamese have all been subjected to persecution in their home city.

In this book, Chad "tells the stories of five marginalized individuals who, over the last two centuries, forged their own notions of belonging in one of Europe’s great cities." Though not famous people, their lives are revealing, speaking to "tensions between exclusionary nationalism and on-the-ground diversity." This aspiring guidebook writer, German-speaking newspaperman, Bolshevik carpenter, actress of mixed heritage coming of age during the Communist terror, and Czech-speaking Vietnamese blogger all "struggle against alienation and dislocation, forging alternative communities in cafes, workplaces, and online. While strolling park paths, joining political marches, or writing about their lives, these outsiders came to embody a city that, on its surface, was built for others."

I'm eager to read this! We can pre-order here.

In this book, Chad "tells the stories of five marginalized individuals who, over the last two centuries, forged their own notions of belonging in one of Europe’s great cities." Though not famous people, their lives are revealing, speaking to "tensions between exclusionary nationalism and on-the-ground diversity." This aspiring guidebook writer, German-speaking newspaperman, Bolshevik carpenter, actress of mixed heritage coming of age during the Communist terror, and Czech-speaking Vietnamese blogger all "struggle against alienation and dislocation, forging alternative communities in cafes, workplaces, and online. While strolling park paths, joining political marches, or writing about their lives, these outsiders came to embody a city that, on its surface, was built for others."

I'm eager to read this! We can pre-order here.

Monday, March 15, 2021

How Quick a Writer Are You?

Writers both new and experienced often bemoan the speed at which they write. People have, of course, a wide range of preferred times and places to write, and approach their work in many different ways. Still, most of us would like to accomplish more than we actually do, especially those of us who have lots of ideas for new projects. Are there effective ways of getting our writing projects done, especially our books, more quickly?

I myself know that I'm capable of writing a book in a short period of time, because I've done it--I wrote In Search of the Magic Theater in three months, during which time I was also completing my PhD and teaching. Admittedly, that's not counting the fact that I first had the idea for it about ten years before I wrote it, and that I'd written a few pages some years prior to writing the whole book. In other words, I had thought about it some ahead of time--but not really very much, because I was in grad school for most of that period and there wasn't much mental space for either reading or writing fiction until I was close to graduation. So the fact that I wrote nearly every word of an entire and publishable novel in three months remains a fairly impressive thing. Years earlier I had written my first finished novel in about the same length of time, a murder mystery that I don't anticipate revising or seeking a publisher for. And in 2019 I wrote another novel in three months, followed by a novella in 2020 that took about the same amount of time. I wrote these three-month novels with a general goal of averaging 2000 words per day, which for me is not a difficult goal if I have a clear idea where I'm going.

Most of my book projects, however, are taking much longer. As in ten years or more. I completed one of those ten-year books in 2019 and have three others that I like to think I could finish if I had a good chunk of time for each. As in, maybe finish one each summer if my teaching and research don't get in the way. (After finishing my novella, I would have liked to finish one of the novels, but the rest of the summer went toward figuring out how to teach remotely in the pandemic, including creating a new course.)

One of the major pieces of advice for writers, at least in the academic world (but true for any writing), is Ass In Chair. Namely, you can't get writing done if you don't settle down and do it. Obvious, but especially important for those who don't enjoy writing, and many scholars don't. Even many fiction writers don't enjoy the writing itself particularly; they enjoy having written. However, I think most fiction writers do enjoy writing, at least much of the time. Why else would we do it?

My colleague Erin Flanagan over in the English department, who teaches novel and short story writing, found an interesting blog post about increasing our productivity, which I offer to you all, fiction or nonfiction writers of any sort. Rachel Aaron, also published as Rachel Bach, writes genre fiction series, so she has more deadlines than some of us do. She wasn't having much trouble managing 2000 words per day, but as a newly full-time writer with a series to write, she wanted to increase her productivity. After all, if she could write 2000 words a day before going to her job, couldn't she write 4000 words a day as a full-time writer?

At first she couldn't. And here I'd jump in to say that in my experience, writing a lot is something that, much like doing pushups or running marathons, you gradually work up to being able to do. Yes, you have to settle down to work, but at first you probably have to write in short increments and then build up how long you can work without getting frustrated or distracted.

Rachel says, "I gathered data and tried experiments, and ultimately ended up boosting my word count to heights far beyond what I'd thought was possible, and I did it while making my writing better than ever before." She began keeping records: "Every day I had a writing session I would note the time I started, the time I stopped, how many words I wrote, and where I was writing on a spreadsheet. I did this for two months, and then I looked for patterns." She discovered where she was most productive (for her, in a cafe with no wifi), and that if she had more than an hour available, she wrote more per hour than if she only had one hour to write (but that beyond seven hours, productivity dropped again). She also found the time of day that she was most productive, which was not the time she thought it would be.

This is something every writer can try--seeing when we are, individually, most productive and then making the best of that time. But Rachel also found two other major factors that improved her productivity. One, in fact, she discovered prior to studying when she was productive. This was to have a good idea in advance where she was going with a scene.

"I wasn't a total make-it-up-as-you-go writer. I had a general plot outline, but my scene notes were things like 'Miranda and Banage argue' or 'Eli steals the king.'" She knew the general direction and liked to let the characters take control. However, "this meant I wasted a lot of time rewriting and backtracking when the scene veered off course." She noted, "Here I was, desperate for time, floundering in a scene, and yet I was doing the hardest work of writing (figuring out exactly what needs to happen to move the scene forward in the most dramatic and exciting way) in the most time consuming way possible (ie, in the middle of the writing itself)."

Instead, Rachel began her writing sessions by jotting down notes about the scene she was about to write: "working out the back and forth exchanges of an argument between characters, blocking out fights, writing up fast descriptions." She says, "Every writing session after this realization, I dedicated five minutes (sometimes more, never less) and wrote out a quick description of what I was going to write. Sometimes it wasn't even a paragraph, just a list of this happens then this then this." This saved her from writing lots of text that went in the wrong direction and had to be cut or rewritten later.

This is not something I myself typically do when writing fiction. For one thing, I'm not usually (other than that mystery novel long ago) writing genre fiction. My characters don't usually have arguments or lots of dramatic action; often what goes on is more internal, and while I do a certain amount of productive, written speculation about what I might want to have happen, most of my best ideas happen in the course of actually writing. But while I don't usually have to do heavy revision of the kind many writers rely on (cutting scenes, turning two characters into one, changing point of view), I'm aware that my "quick" novels get written in a different manner, closer to what Rachel does, than my ten-year novels. My quick novels have more of a structure from the outset and I usually write them starting at the beginning and in the order of the chapters, ending with the end. My ten-year novels do have a structure from the outset, but it's a more open, fluid one. They're more likely to be a Bildungsroman, or some other less plot-driven form. My scenes aren't written in any particular order, I just will have an idea for a scene and know it goes somewhere in the middle. Gradually the scenes accrete and their order and transitions get worked out.

So although I'd like to write more of my novels more quickly, I'm not sure whether Rachel's advice about starting the writing session with quick notes will always work for me, but it should work for at least some of what I write, and should certainly help writers who like to outline in advance to some extent.

Rachel's third breakthrough was about enthusiasm. "Those days I broke 10k were the days I was writing scenes I'd been dying to write since I planned the book. ... By contrast, my slow days (days where I was struggling to break 5k) corresponded to the scenes I wasn't that crazy about." She began to focus on figuring out how to either get rid of the scenes that excited her less, or make them more interesting.

Again, since I write a different kind of fiction than Rachel, this isn't quite what I struggle with, but I have a parallel situation. The scenes that I put off writing aren't those that I find dull, really, but are more often those that I don't feel I know how to write yet--that I haven't researched something enough, or where I'm unsure how to do a transition. When wrapping up the ten-year novel that I finished in 2019, this kind of thing was my main focus, and often I found I could handle the problem by simply writing a few lines, a summary of what I wanted to say, and that was enough. Not every scene or transition needs to be fleshed out in detail.

What Rachel does not count here is the time spent plotting the novel and figuring out its overall shape. It's clear that she does this prior to writing the chapters, and this is something that can take significant amounts of time. I know I often think about a novel idea for years before I feel ready to start, even though I may not have more than a vague idea of the structure by the time I start. For me, having several simultaneous projects means that when I'm not focused on one in particular (writing that quick novel or finishing a ten-year novel), I'm never stuck because I can always work on a different project. I'm always curious how other writers structure their work and I'm not above stealing basic structures and plots.

Rachel says, finally, "There are many fine, successful writers out there who equate writing quickly with being a hack. I firmly disagree. My methods remove the dross, the time spent tooling around lost in your daily writing, not the time spent making plot decisions or word choices. This is not a choice between ruminating on art or churning out the novels for gross commercialism (though I happen to like commercial novels), it's about not wasting your time for whatever sort of novels you want to write." I agree with her. While I don't think all novels can be written quickly, I'm all for writing more efficiently.

After blogging about writing more productively, Rachel went on to write a book about her method, 2000 to 10,000: How to Write Better, Write Faster, and Write More of What You Love, which you can buy on Amazon for Kindle at a very reasonable price.

I myself know that I'm capable of writing a book in a short period of time, because I've done it--I wrote In Search of the Magic Theater in three months, during which time I was also completing my PhD and teaching. Admittedly, that's not counting the fact that I first had the idea for it about ten years before I wrote it, and that I'd written a few pages some years prior to writing the whole book. In other words, I had thought about it some ahead of time--but not really very much, because I was in grad school for most of that period and there wasn't much mental space for either reading or writing fiction until I was close to graduation. So the fact that I wrote nearly every word of an entire and publishable novel in three months remains a fairly impressive thing. Years earlier I had written my first finished novel in about the same length of time, a murder mystery that I don't anticipate revising or seeking a publisher for. And in 2019 I wrote another novel in three months, followed by a novella in 2020 that took about the same amount of time. I wrote these three-month novels with a general goal of averaging 2000 words per day, which for me is not a difficult goal if I have a clear idea where I'm going.

Most of my book projects, however, are taking much longer. As in ten years or more. I completed one of those ten-year books in 2019 and have three others that I like to think I could finish if I had a good chunk of time for each. As in, maybe finish one each summer if my teaching and research don't get in the way. (After finishing my novella, I would have liked to finish one of the novels, but the rest of the summer went toward figuring out how to teach remotely in the pandemic, including creating a new course.)

One of the major pieces of advice for writers, at least in the academic world (but true for any writing), is Ass In Chair. Namely, you can't get writing done if you don't settle down and do it. Obvious, but especially important for those who don't enjoy writing, and many scholars don't. Even many fiction writers don't enjoy the writing itself particularly; they enjoy having written. However, I think most fiction writers do enjoy writing, at least much of the time. Why else would we do it?

My colleague Erin Flanagan over in the English department, who teaches novel and short story writing, found an interesting blog post about increasing our productivity, which I offer to you all, fiction or nonfiction writers of any sort. Rachel Aaron, also published as Rachel Bach, writes genre fiction series, so she has more deadlines than some of us do. She wasn't having much trouble managing 2000 words per day, but as a newly full-time writer with a series to write, she wanted to increase her productivity. After all, if she could write 2000 words a day before going to her job, couldn't she write 4000 words a day as a full-time writer?

At first she couldn't. And here I'd jump in to say that in my experience, writing a lot is something that, much like doing pushups or running marathons, you gradually work up to being able to do. Yes, you have to settle down to work, but at first you probably have to write in short increments and then build up how long you can work without getting frustrated or distracted.

Rachel says, "I gathered data and tried experiments, and ultimately ended up boosting my word count to heights far beyond what I'd thought was possible, and I did it while making my writing better than ever before." She began keeping records: "Every day I had a writing session I would note the time I started, the time I stopped, how many words I wrote, and where I was writing on a spreadsheet. I did this for two months, and then I looked for patterns." She discovered where she was most productive (for her, in a cafe with no wifi), and that if she had more than an hour available, she wrote more per hour than if she only had one hour to write (but that beyond seven hours, productivity dropped again). She also found the time of day that she was most productive, which was not the time she thought it would be.

This is something every writer can try--seeing when we are, individually, most productive and then making the best of that time. But Rachel also found two other major factors that improved her productivity. One, in fact, she discovered prior to studying when she was productive. This was to have a good idea in advance where she was going with a scene.

"I wasn't a total make-it-up-as-you-go writer. I had a general plot outline, but my scene notes were things like 'Miranda and Banage argue' or 'Eli steals the king.'" She knew the general direction and liked to let the characters take control. However, "this meant I wasted a lot of time rewriting and backtracking when the scene veered off course." She noted, "Here I was, desperate for time, floundering in a scene, and yet I was doing the hardest work of writing (figuring out exactly what needs to happen to move the scene forward in the most dramatic and exciting way) in the most time consuming way possible (ie, in the middle of the writing itself)."

Instead, Rachel began her writing sessions by jotting down notes about the scene she was about to write: "working out the back and forth exchanges of an argument between characters, blocking out fights, writing up fast descriptions." She says, "Every writing session after this realization, I dedicated five minutes (sometimes more, never less) and wrote out a quick description of what I was going to write. Sometimes it wasn't even a paragraph, just a list of this happens then this then this." This saved her from writing lots of text that went in the wrong direction and had to be cut or rewritten later.

This is not something I myself typically do when writing fiction. For one thing, I'm not usually (other than that mystery novel long ago) writing genre fiction. My characters don't usually have arguments or lots of dramatic action; often what goes on is more internal, and while I do a certain amount of productive, written speculation about what I might want to have happen, most of my best ideas happen in the course of actually writing. But while I don't usually have to do heavy revision of the kind many writers rely on (cutting scenes, turning two characters into one, changing point of view), I'm aware that my "quick" novels get written in a different manner, closer to what Rachel does, than my ten-year novels. My quick novels have more of a structure from the outset and I usually write them starting at the beginning and in the order of the chapters, ending with the end. My ten-year novels do have a structure from the outset, but it's a more open, fluid one. They're more likely to be a Bildungsroman, or some other less plot-driven form. My scenes aren't written in any particular order, I just will have an idea for a scene and know it goes somewhere in the middle. Gradually the scenes accrete and their order and transitions get worked out.

So although I'd like to write more of my novels more quickly, I'm not sure whether Rachel's advice about starting the writing session with quick notes will always work for me, but it should work for at least some of what I write, and should certainly help writers who like to outline in advance to some extent.

Rachel's third breakthrough was about enthusiasm. "Those days I broke 10k were the days I was writing scenes I'd been dying to write since I planned the book. ... By contrast, my slow days (days where I was struggling to break 5k) corresponded to the scenes I wasn't that crazy about." She began to focus on figuring out how to either get rid of the scenes that excited her less, or make them more interesting.

Again, since I write a different kind of fiction than Rachel, this isn't quite what I struggle with, but I have a parallel situation. The scenes that I put off writing aren't those that I find dull, really, but are more often those that I don't feel I know how to write yet--that I haven't researched something enough, or where I'm unsure how to do a transition. When wrapping up the ten-year novel that I finished in 2019, this kind of thing was my main focus, and often I found I could handle the problem by simply writing a few lines, a summary of what I wanted to say, and that was enough. Not every scene or transition needs to be fleshed out in detail.

What Rachel does not count here is the time spent plotting the novel and figuring out its overall shape. It's clear that she does this prior to writing the chapters, and this is something that can take significant amounts of time. I know I often think about a novel idea for years before I feel ready to start, even though I may not have more than a vague idea of the structure by the time I start. For me, having several simultaneous projects means that when I'm not focused on one in particular (writing that quick novel or finishing a ten-year novel), I'm never stuck because I can always work on a different project. I'm always curious how other writers structure their work and I'm not above stealing basic structures and plots.

Rachel says, finally, "There are many fine, successful writers out there who equate writing quickly with being a hack. I firmly disagree. My methods remove the dross, the time spent tooling around lost in your daily writing, not the time spent making plot decisions or word choices. This is not a choice between ruminating on art or churning out the novels for gross commercialism (though I happen to like commercial novels), it's about not wasting your time for whatever sort of novels you want to write." I agree with her. While I don't think all novels can be written quickly, I'm all for writing more efficiently.

After blogging about writing more productively, Rachel went on to write a book about her method, 2000 to 10,000: How to Write Better, Write Faster, and Write More of What You Love, which you can buy on Amazon for Kindle at a very reasonable price.

Labels:

advice,

blogs,

books,

fiction,

good ideas,

observations,

writers,

writing

Sunday, March 14, 2021

I do an Interview about Magnetic Woman

Clifford Garstang has begun a wonderful series of short interviews with authors of new books, and I'm thrilled to say that he has included an interview with me about Magnetic Woman! Check it out--and be sure to take a look at his interviews with other authors as well. You'll probably see more than one book you'd like to read!

Clifford Garstang is the author of five works of fiction including the novels Oliver’s Travels and The Shaman of Turtle Valley and the short story collections House of the Ancients and Other Stories, What the Zhang Boys Know, and In an Uncharted Country. He is also the editor of the acclaimed anthology series, Everywhere Stories: Short Fiction from a Small Planet.

Clifford Garstang is the author of five works of fiction including the novels Oliver’s Travels and The Shaman of Turtle Valley and the short story collections House of the Ancients and Other Stories, What the Zhang Boys Know, and In an Uncharted Country. He is also the editor of the acclaimed anthology series, Everywhere Stories: Short Fiction from a Small Planet.

Friday, March 12, 2021

Author Copies Arrive!

Finally, finally, finally, after the disappointment of the printing errors, the corrected, perfected print run of Magnetic Woman is definitely available and out there in the world and I have received my author copies! Now to package them up and send them to the various museums and organizations that gave me images in exchange for a copy or two of the book... and of course the copy to send to my immediate family!

Monday, March 1, 2021

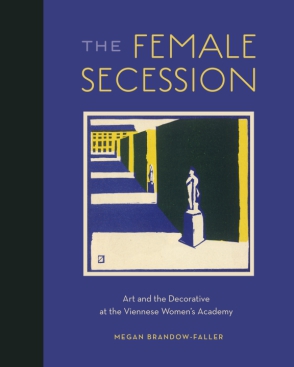

The Female Secession

Is it great or is it a bit sad that so many interesting books are coming out during the pandemic? I really don't know--on the one hand there is plenty to read (for anyone who has time, which many of us don't really just now), and on the other hand it's harder to promote books when we can't meet in person and often we just feel that the last thing we want to see is another Zoom-type event.

Nonetheless, here's another want-to-have title for those of us who study art/design history, Central Europe, and/or women's/gender history! Megan Brandow-Faller's The Female Secession: Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women’s Academy traces the history of the women’s art movement in Secessionist Vienna from its origins in 1897, at the Women’s Academy, to the Association of Austrian Women Artists and its radical offshoot, the Wiener Frauenkunst and "draws a direct connection to the themes that impelled the better-known explosion of feminist art in 1970s America." I know I want to learn more!

Click here for more information and to order your copy.

Nonetheless, here's another want-to-have title for those of us who study art/design history, Central Europe, and/or women's/gender history! Megan Brandow-Faller's The Female Secession: Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women’s Academy traces the history of the women’s art movement in Secessionist Vienna from its origins in 1897, at the Women’s Academy, to the Association of Austrian Women Artists and its radical offshoot, the Wiener Frauenkunst and "draws a direct connection to the themes that impelled the better-known explosion of feminist art in 1970s America." I know I want to learn more!

Click here for more information and to order your copy.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)